Thinking Resilience

“Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.” Andre Gide

Introduction

I gave a little content warning about my main topic last time. A couple of people even told me they were interested to hear what I had to say. I have been busy this week talking about this at a series of roadshows for the National Lottery Heritage Fund and it feels really relevant to people. If, however, you’re sick of thinking about resilience, I’m sorry and do skip to the Tactics Tomato playlist now and accept it as my apology for repetition.

Funding resilience

Am I still going on about creative resilience? I am.

(The first time I wrote about it was on my Arts Counselling blog in February 2009, for those that are interested. I was picking a trail from Andrew Taylor, I think.)

You can now read some long-memoried thoughts courtesy of the good women of Arts and Business Northern Ireland, who asked me to write about what makes a resilient organisation ahead of their annual Funders Exchange next month. I threw in some thoughts for funders.

No surprises

I realised when I was writing the blog that there was a parallel between the conversations and observations I and many others were having about the mix of precarity and resilience currently obvious in the arts and cultural sector and the discussions around climate change.

The effects of climate change should not be a surprise to us. People have been pointing out the inevitable consequences of living as if we had the resources of several planets, not just one, for decades.

Similarly the gradual weakening and shrinkage of many cultural organisations is now becoming visible to the naked eye, decades after people began to worry about the arts of living and dying. (Hat tip to Mission Models Money especially, as always.)

Shorter festivals, with fewer shows, and smaller productions. Shorter tours and more remounted shows. Smaller casts. Less ambitious sets. Venues quietly reducing the number of days and nights they open. Fewer staff covering more work. For a long time you could squint and miss it. But no longer.

Deficits and other symptoms

Research by Sarah Thelwall’s MyCake and Arts Professional shows the dire state of many organisations’ finances: a combined deficit of £117.8m in 2023 across a group of 2800 whose accounts could be analysed back to 2018. This compares to the position in 2022 when the collective surplus was £152.4m. So the rapid decline across those organisations is more than £270M. As Sarah points out this begs some big questions, including which organisations and sector should we build the future around? (I’ll return in the future to how we might begin to think about that question.)

Other parts of the system are also creaking and failing. Success rates for funding applications have been on a fairly consistent downward curve for more than a decade. Some trusts and foundations are concluding that this now creates an unsustainable burden on applicants. Some (not confined to the arts) have closed their funds while they work out what to do for the best. Others are spending out entirely. The knock-on effects include a big increase in time needed for fundraising, as more applications are likely to be necessary. (And although we may be personally resilient against rejection, given how intrinsic that is to culture, there is also attritional damage there.)

Paul Hamlyn Foundation recently published an admirably transparent blog about their experience of the first round of their new Arts Fund, so far. This illustrates several challenges really clearly. First and fundamentally is that it’s impossible for one of the main arts-funding trusts to do more than scratch demand. (For Round One of the new fund, they received 345 applications, more than in a typical year.)

The Foundation – quite rightly, and excitingly – still have big ambitions for the fund: social justice and structural change. As Shoubhik Bandopadhyay sets out, one reason strong applications may not make the longlist is “our desire is to support organisations working towards long-term structural and cultural change in the sector, rather than further honing the existing model”. But this is challenging for applicants – how exactly do you that while operating in the current framework of actually-existing arts funding and power structures?

A climate crisis

As I argue in the ABNI blog, these things are to the arts sector as melting icecaps and more frequent 'weather incidents' are to the environment: a climate crisis emerging from long-term change and our seeming inability to act. In the cultural sector this freezing before the issues allows a host of conditions to spread: chronic undercapitalisation, drastic reductions in funding, the cost of living/producing, imbalances of power and reward and systemic exclusion of people from less privileged backgrounds. To name but a few.

I was recently invited to think about where does financial resilience come from, if the old ‘dependence’ on funders and funding can no longer be relied on to a sufficient level? The same place as other aspects of creative resilience: being good at what you do, and what you do being valuable and valued, loved even. All the inventive, innovative, entrepreneurial canniness and nouse in the world will not save a sector or an organisation falling into disrepair if it is not valued and valuable. (And, yes, being valued by those with privilege can preserve some practices long beyond their creative peak.)

As I’ve discussed previously new cases for funding resilient culture will need to be made if the new UK government is to turn warm words into actual heat(ing). The main problem with publications such as the recent report from the Fabian Society, Arts for Us All, is that at strategy and commitment level it is little different from the words the Tory government used to use. Everyone will say they believe talent exists everywhere, but opportunity doesn’t. Everyone will say they want young people to have access to the arts.

The previous government said that and then acted in ways that made those aspirations impossible. I checked back to what I wrote about the 2016 (Vaizey-era) DCMS White Paper and it feels really relevant to such current policy arguments. We can redesign our strategies and our models (of activity, business and investment) all we want, and they might help, but not as much as new money. I’d be taking the income from VAT on public school fees and putting it into arts and culture to support those voices and stories squeezed out by the public school boys and girls.

Some say new money for culture and cultural education is impossible: we know this is not true. Be reasonable, demand the impossible etc…

New models of investment

We need new sources and models of investment, probably mixing loans and grants, that build infrastructure and income generation skills and strengths. One example just launched is Figurative, a redesigned and independent successor to the Arts Impact Fund, now that NESTA have quietly but scandalously moved away from the arts. (Why was that portion of their original endowment not passed on an arts funder?) This is a welcome move to a social enterprise way of thinking that will encourage organisations – perhaps collaboratively – to think about their underlying business models as much as their outputs.

It does, however, run the same risk as the kind of ambition shown by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and others, potentially heaping further ‘system changing’ outcomes onto already pressurised cultural organisations with their own missions and visions. I have a nagging fear this may lead to what I will call Mutual Fairytale Syndrome, where organisations design theories of change with barely believable long-term outcomes from short-term funding inputs, which funders barely believe but accept in preference to more modest potential results.

Four suggestions

In the ABNI blog I make four suggestions for funders (and implicitly for those seeking their investment):

Invest in collaborative and collective resilience-building, including place-based or sub-sectoral/specialist networks

Invest in individual organisations based on commitment to mission, focussing more on building organisational capacity for the long-term (including covering core costs during that process), than on buying outputs and outcomes

Focus on developing asset-based mindsets and skills that create ongoing revenue and community involvement, activities, including use of loans and other investment models such as bonds

Invest not on an asset-by-asset basis but on the basis of building a resilient cultural infrastructure for communities, places and practices, informed by strong intelligence and audit of the relevant landscape/ecology.

Want to read even more about creative resilience?

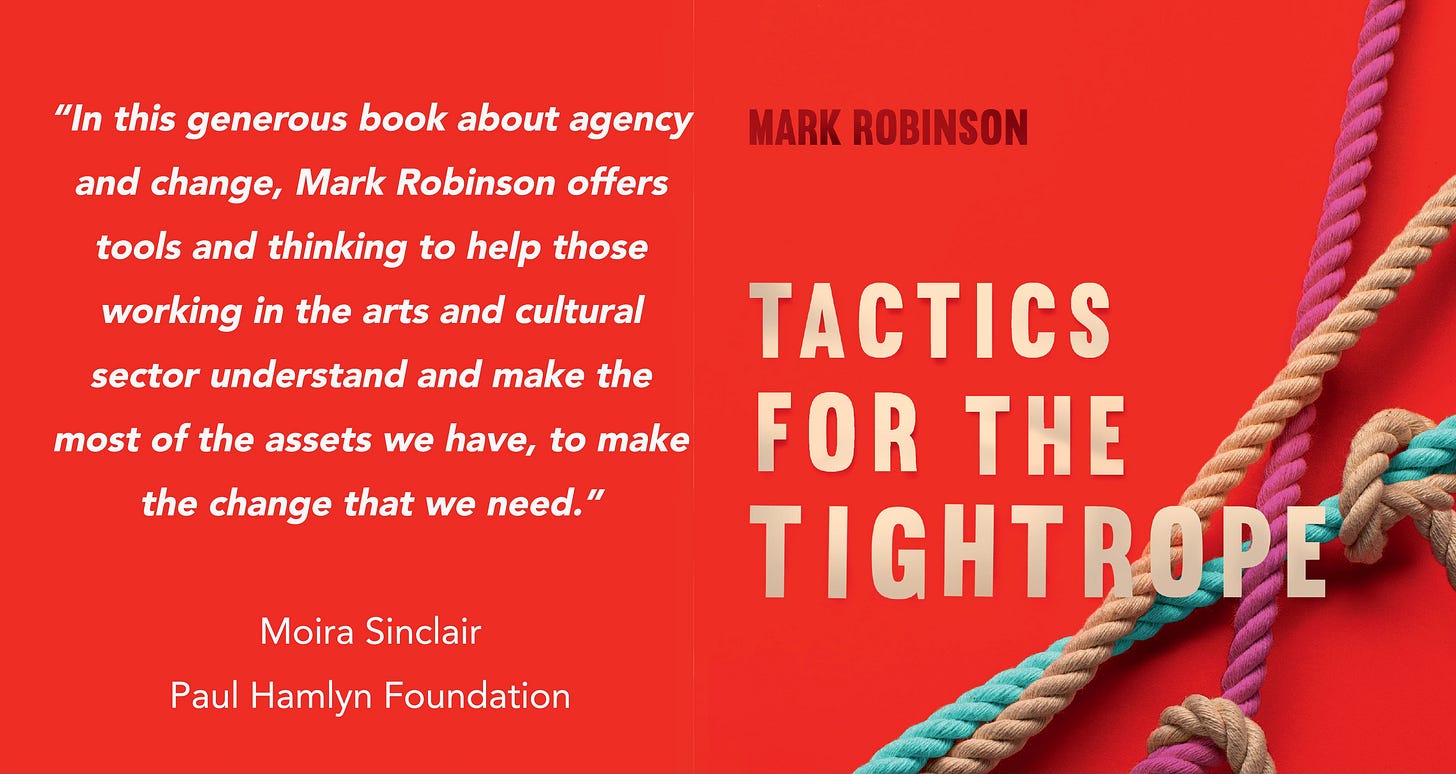

If you’re new to my descriptions and arguments about how we might have more creative, more resilient cultural organisations, sectors and communities, I highly recommend reading my highly acclaimed (well, by a few people anyway) book published by Future Arts Centres in 2021, Tactics for the Tightrope: Creative Resilience for Creative Communities. Well, I would, wouldn’t I?

You can still buy a beautiful hard copy to invite conversation on trains or you can download it for FREE. All the chapters – and the tools for use in your creative communities – are also available for FREE download at tacticsforthetightrope.com.

Tactics Tomato

I’m very aware that resilience needs an allergy warning for some people. Here’s 27 minutes of songs by way of #sorrynotsorry for #repetition. Remember to take 5 minutes off when it ends.